Bringing Life to a Food Desert

“What do you love about your grocery store?” an interviewer asks California locals on a Youtube video. Upbeat folksy music plays in the background as people respond.

“I love that it has local products,” says one woman from Berkeley.

“It feels like a community,” responds an elderly gentleman from Fairfax.

“I can walk to this store,” says a Daily City man.

“It’s got a lot of organic food. It’s local,” answers a woman from Alameda.

“There hasn’t been a grocery store in West Oakland since the nineties,” replies a woman.

The music grinds to a halt.

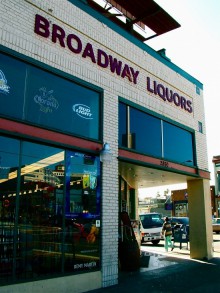

Over the past half century, West Oakland, just across the Bay from San Francisco, has faced the economic decline that has plagued many of America’s urban centers since World War II. As populations and shopping have moved farther from urban centers, day-to-day survival in these areas have become more challenging and more costly. Today, many refer to West Oakland as a “food desert,” a place that is better known for its liquor and convenience stores than its supermarkets.

A 2008 study conducted by the Alameda County Public Health Department tells the story of decline. In 1950 there were 140 traditional food stores, but by 2000, there were just a handful residents. Some of this perhaps was due to population decline, but much of it was due to economic decline.

The rise of the liquor store

How did a place that was once home to one of the nation’s largest middle-class African American communities and a bustling hub for San Francisco’s jazz and blues scene end up here? What are the factors that have contributed to West Oakland’s decline, particularly the decline of its food economy? And what are West Oakland residents doing today to increase their food access, against the odds?

West Oakland once had a vibrant food system, replete with small grocery stores and plenty of backyard gardens. But around the middle of the twentieth century, as suburbia began to sprawl outward from San Francisco’s urban core, federal, state, and local government began seizing parts of West Oakland for projects like the BART railway and 1949 Cypress Freeway, which split the neighborhood in half and isolated the area from the rest of the Oakland community. As the area bowed to these factors outside of its control, banks began a practice of redlining—a process now illegal, in which certain areas were marked as “undesirable” for commercial and residential investment. With less access to capital for business development, populations begin fleeing urban neighborhoods, creating a downward spiral of economic decline. Local supermarkets and mom-and-pop grocery stores, facing declining revenues, either shut their doors or left West Oakland.

While the number of food stores was decreasing the number of liquor stores began multiplying, selling higher-priced items like alcohol and cigarettes, and charging higher-than-normal prices for a small selection of food items. Today there are more than 50 liquor stores in West Oakland, a handful of small corner stores, and one food co-op.

Stacking the odds

As West Oakland’s economy has diminished, the rates of un-health and disease among its residents have soared. According to the Alameda County Health Department, an African American adult living in West Oakland is twice as likely to be hospitalized for and die of heart disease or cancer than a white adult of the same age living in nearby Oakland Hills; three times as likely to die from a stroke; and five times as likely to be hospitalized for diabetes. Ultimately, an African American adult living in West Oakland can expect to die almost 15 years earlier than his white counterpart in Oakland Hills.

Is the correlation between West Oakland’s deteriorated food economy and its health a causal one? Inevitably, there will be outsiders who will glance at the health problems of those in West Oakland and attribute them to poor choices. After all, if one wants to eat for health, isn’t a little willpower the only required ingredient? Certainly personal choices are a critical factor in healthy living, but for people living in blighted urban centers, these choices can carry high costs.

Consider the following scenario: A working single mother from West Oakland wants to put healthy, nutritious food on the table for her two young children. She makes $26,000 a year working 40 hours a week as a janitor. She doesn’t own a car, and is therefore dependent upon public transportation to get her to one of the closest grocery stores, 3 miles away in East Oakland. She packs up her children to head to the grocery store. A 15-minute walk, a train, and a bus ride later, she arrives at the store, where she purchases a week’s worth of meat, produce, and dry goods. She then totes her children and six bags of groceries back home, retracing her steps in no less than 30 minutes. The next week, despite her continued interest in feeding her family a healthy diet, she opts for the five-minute walk to the corner liquor store, where she is able to choose from a small selection of over-priced old produce and highly-processed high calorie packaged food items.

This scenario, while fictional, is representative of the common experience of West Oakland residents. It’s a week-to-week routine that would stretch the resolve of even the most resourceful shopper. According to 2000 census data, almost 20 percent of households in Oakland didn’t have a car (with the rate being as high as 35 percent in West Oakland), compared to the national average of 11 percent. Low-income households (making less than $20,000) in West Oakland spend over half of their income on public transportation, according to the Alameda study.

But transportation isn’t the only roadblock West Oakland residents face in achieving a nutritious diet. When it comes to education in healthy eating, there isn’t too much to be found in West Oakland.

“There’s not too much exposure to an alternative to junk food,” said Saqib Keval, an employee of People’s Grocery, a local nonprofit. “If every day of your life you’re being told that Cheetos are good for you and that’s all you have access to, that’s what you’re going to eat.”

Locals know best

It was the need to help residents in the nutritional wasteland that West Oakland had become that gave birth to People’s Grocery. Founded a little over ten years ago, People’s Grocery has been helping West Oakland residents develop homegrown solutions to their challenges in accessing healthy food.

Brahm Ahmadi, a young community organizer working in low-income neighborhoods in the Bay Area started People’s Grocery. It wasn’t actually a grocery store, but an effort—seeded with funding from independent donors—to improve both the health of West Oakland residents and to improve the local economy through rebuilding the community’s food system.

“People would raise this issue—‘We don’t have access to healthy food,’ ” explains Ahmadi. “It kept coming up over and over again. I was pretty astounded by the data . . . the extent to how underserved the community was, and what people had to do to get to food sources . . . we thought it was an issue to be dealt with, and at the time nobody in West Oakland really was.”

Since Ahmadi started People’s Grocery in 2002, the organization has piloted multiple projects that have created alternative food sources for over 9,000 of West Oakland’s approximate 25,000 residents, while contributing $393,000 toward the local economy, in the form of direct revenue. Two of its first endeavors, The Mobile Market, a food truck that provided fresh produce on a weekly basis to West Oakland residents, and the Grub Box, an affordable CSA (community supported agriculture) program, have been replicated across the country.

From the beginning, People’s Grocery has been committed to harnessing resident wisdom to find the most workable solutions to the community’s needs.

“Those most affected by the problem will play the most prominent role in the solution,” Ahmadi explains.

Perhaps the best example of this is an effort that was piloted two years ago in 2011 called the Growing Justice Institute which empowers a handful of specially selected local individuals to start income-generating businesses that will also improve the community’s health and food security.

Here’s how it works: interested members of the community submit proposals for projects they’d like to undertake, everything from healthy cooking classes to community gardens. The applicants who are selected receive a small stipend from People’s Grocery to cover basic expenses until their business gets off the ground. For the first several months of the Institute, the group works through a series of topics such as food economics, community organizing, urban agriculture, the components of starting a food business, and project management, so that they are equipped to get their businesses off the ground.

Since 2011, five types of resident projects have taken off:

Since 2011, five types of resident projects have taken off:

- Two catering companies, one that caters raw, vegan lunches to residents at a senior center

- A curriculum that will be implemented in West Oakland schools to help minority youth understand their historical culture of food and farming

- A design for an off-the-grid community that will incorporate urban farming

- A holistic health care company that provides meal planning and dietary coaching for patients at local hospitals, and

- A non-cash network that is exploring bartering, time banking, and peer lending circles as a way to build community vitality among West Oakland residents

Of the six who have launched their projects, all have faced huge hurdles getting there.

“When we started, everyone in the group had been houseless at some point,” says Keval, who runs the program. “[Some] lived in houses that were foreclosed upon. [Some faced] illnesses. Three fellows dealt with death in immediate families caused by violence in the community.”

Despite these challenges, the group has begun to see fruit grow from their efforts. Perhaps more than anything, the participants experience the satisfaction of contributing to something potentially permanent—something that will leave a positive print on their community.

Reinventing the market

In any given year, West Oakland residents spend close to $60 million on food, the same market value as a nearby middle-income community with half the population. The main difference is that West Oakland has twice the population as the other community. And, in West Oakland, a large percentage of that almost $60 million is being siphoned away from the community, as many West Oakland residents travel to grocery stores in other communities to do their shopping.

But what if that $60 million could be funneled back into the community?

In 2009, Ahmadi decided it was time to take his seven years of experience in food organizing to the next level. He resigned from his position as executive director at People’s Grocery and set out to raise capital to bring a commercial grocery store back to West Oakland.

Early on, Ahmadi realized that he couldn’t just start a traditional supermarket—a new business model was required for local circumstances in West Oakland. Supermarkets, which carry an enormous amount of inventory, are designed to serve customers who shop once per week and spend on average $75 to $100 per visit. In contrast, the typical customer from West Oakland spends approximately $25 to $50 per visit and shops a couple of times per week, partly because of budget constraints and partly because many West Oakland residents can only purchase as many groceries as they can carry home on foot or by bus. Similarly, land use restrictions due to lead contamination and other issues make it very difficult to acquire a plot large enough on which to build a suburban-sized supermarket.

So Ahmadi and a team of five developed a plan for People’s Community Market, a 15,000-square-foot “small-format, full-service neighborhood food store” that would also serve as a social hub and health resource center. The Market would offer “a more edited and targeted product mix,” eliminating redundant items in each food category, and ultimately better aligning with “the way people really spend their money.” By keeping inventory small, the store would still be able to offer affordable, healthy food choices to its customers, but could keep costs low by avoiding the wastefulness and money drain associated with inventory shrinkage. The venture would also create 50 new jobs, with an approach of hiring, training, and investing in employees as valuable assets of the company.

“Working in a grocery store is hard work, and if you don’t have incentive to stick around, you won’t,” Ahmadi explains. “But independent grocers sometimes have employees who stay with them for at least 10 or 15 years.”

Employees would receive life skills training as well as access to other services the Market would provide, such as healthy food demonstrations, and counseling on health and nutrition.

As of August 2013, People’s Community Market, Inc. (PCM) had sold approximately $640,000 in shares to California investors, with an individual investment minimum of $1,000, a 3% annual interest, and a 1% store credit. Many investors are nearby Oakland residents who want to help create food access for their neighbors.

“As an Oakland resident, I know how lucky I am to live in between a farmers market and a full-scale grocery store, while my neighbors are not so fortunate,” writes one investor. “I am thrilled to be able to invest in People’s Community Market, an exciting and critical next step for West Oakland and hope others join me.”

The goal is to reach $1.2 million through direct public offerings (DPO) and then acquire the remaining two-thirds of the funding through a one-time 12-year- term loan from California FreshWorks Fund, a public-private loan fund supported by partners ranging from Charles Schwab to Kaiser Permanente to the State of California. Ahmadi says they hope to break ground at one of three possible sites in the fall of 2014.

Although Ahmadi admits that putting a grocery store in West Oakland won’t erase the deeper issues of poverty, crime, and pollution that have plagued the neighborhood for so long, he does see it as a catalyst that can spark community transformation and help return capital investment to the community.

“Food . . . is an effective tool to organizing and effecting change. It’s about people, it’s about community, and it’s about health.”